Hydraulics

In this our “liquid modernity” and the vaporous Capitalism of flows, control becomes a matter of hydraulics.

In hydraulics, we encounter something called the “Shearing Point” (or “Yield Point”). This is an empirical parameter, closely connected to the notion of Plastic Viscosity (PV) and concerns the point where the resistance of the fluid against deformation breaks down and the matter starts to flow. This point is achieved through the pressure of rapid movement: the acceleration of the force that moves the fluid. In laboratories, this is achieved by a rotary acceleration device (a “viscometer”) akin to the machines used to train astronauts for multiple-G pressures encountered in high acceleration situations. When the plastic fluid shears, it “yields” to the outside force (“shearing stress”) and flows by increasing speeds through whatever conduit available, more and more frictionless and fluid.

The reproduction of the subject of capital is the result of progressive and interminable experiments in acceleration aimed at more effectively reaching the shearing point of the human organism. In order to efficiently shear a fluid with any given PV, one would need to speed it up to the point that it yields its plasticity and becomes analogous to a spring pulled by too strong a force, thereby losing its essence as flexibility and compression.

In Cybernetic Capitalism, the goal is to reach or approach this point of no-return where nothing remains from the previous form of life or existence. The effect is to minimize or nullify all plasticity, as well as the individual’s tendency to put down roots, calcify, jellify, become habituated, sedentary, non-flexible. The machine – the non-representational intelligence that defines the cybernetic organ – has no shearing point, or rather it can be sheared at will and at almost no cost by a direct application of exterior force. In programming, this is usually achieved with an “init()” function, which sets all weights and matrices to zero, preparing the Neural Network to re-start learning, to contract new behavioral habits without any friction with its past. We, as human organisms, are creatures of habit and cannot function without different levels of habituation. The question that faces us today – the question that capital asks from us – is how much alteration is possible? How much self-correction, how much reevaluation and amnesia can we handle, and more importantly at what rate of time?1 All existing examples of conscious modification, of habituated behaviors are finally lengthy processes of counter-habituation, and as such are deeply ineffective for the capitalist society (hence the problems of re-integration; what is demanded is habitlessness, not a change of habits). Habit, in the consumer, equals the sin of addiction while the latter starts to lose its proper meaning in being applied to all habits that resist quick dishabituation, hindering the individual from the realization of maximum potentiality through time.

The workings of the human organism do not allow for a sudden amnesia and change of habits at lower levels of abstraction. The fleshy limitation of human bodies and brains necessitate slow procedures of individuation and self-correction/development. Given the economic reality of Cybernetic Capitalism and the growth of machines replacing laborers of all sorts and in all sectors, however, the workings of human organisms are evaluated and judged by machinic standards, with cybernetic criteria of efficiency and as such they are always bound to lose at every turn. Human organisms are extremely difficult to effectively manipulate from the outside (as a black-box), because at the end there is the matter of the flesh and the limits it imposes on speed and efficiency.

There are certain forms of the human condition, however, that approach (and only approach) the machinic ideals of hyper-adaptivity in capitalism – states where shearing is easier and more cost-effective. In Spinoza’s tale of the zombie poet2 what is discussed as illness is in fact the attaining of the shearing-point of a human subject: how much can the poet change before he becomes someone entirely different? When does the poet yield to the forces of becoming and becomes Other? The “parts” of the poet are rearranged, his habits destroyed, his subjectivity sheared through a sudden illness. This illness, the lowered threshold of shearing stress, is what helped Nietzsche to create new ideas and in modifying his thought (as he mentions in his journals). They are sheared into another just as the famous “patient H. M.” was sheared by an iron rod cutting through his skull, physically and very directly altering his behavior by changing the brain-matter and thus the developed neural circuits.3

These examples of shearing as illness belong to distant times and this is why their traumatic character is evident (or because traumatic illness was the necessary form of accelerated shearing). The illness of “destructive plasticity;” the motion-sickness of the contemporary prosumer, “the new wounded” (as Malabou says) hurling through a carousel of consumption and production, however, is much more subtle and much less openly traumatic because much less differentially is produced. The speed of all life in general has increased to such a high level that the requisite force-acceleration necessary to achieve shearing is relatively lowered and differentially small. The threshold of shearing has decreased to the degree that life has been accelerated under Cybernetic Capitalism; this is especially evident in urban centers and, demographically, among the Millennials. The condition of the prosumer-organism in Cybernetic Capitalism is a form of illness or motion-sickness (that transforms into a psychic dimension, becoming akin to what Hegel called the “sleeping soul”) as the effect of the shearing-stress exerted in attempts to maximize adaptivity through minimizing plasticity (or rather the stability that is inherent in plasticity). Plasticity consists of resistance to deforming forces, a resistance to flowing. As such it has to be minimized so that by approaching total liquefaction (or rather, vaporization) the subject of capitalism can also approach the machinic standard of efficiency.

The impact of these processes of shearing, these becoming-machinic of life and action, is far greater than what we are setting out in terms of the individual here. In his discussion of “l’économie de l’incurie,” (“the careless economy”) Bernard Stiegler insists on demonstrating how the short-circuiting of the subject includes the “systematic destruction” of “care”, for care cannot mean anything in the inhuman temporality, the inhuman speed of the Cybernetic Organon. In fact care becomes obsolete as circumspection, as the most basic and practical relation to the world is substituted by adaptive machines enacting a homeostasis of the environment. Here the human organism will become progressively cut off from a direct interaction with and experience of the world and how this means the effacement of all “savoir-vivre” (knowing how to live) or the set of practices and forms that allow us to realize a collective individuation of a community, a being-together:

By what I call here “savoir-vivre” … I mean the collective production of the rules of “being together”, which marketing has entirely short-circuited during the last decades by imposing ways of life [“modes de vie”] that don't create any more such knowledge of being together, but, quite on the contrary, decompose the societies into gregarious masses…4

Alienation Space and Exodus in Time

Man is a species-being, not only because in practice and in theory he adopts the species... as his object … also because he treats himself as the actual, living species; because he treats himself as a universal and therefore a free being. (Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844)5

Already in the 19th century, Marx sensed the strange condition of proletarized human beings subject to Capital, their assimilation into its circuits, their loss of deliberative and reflective judgment and free self-consciousness – individuals alienated from their species and the life of the species as being-together. Marx speaks of this in terms of Entfremdung (“alienation”) and his analyses of alienation as the loss of self and the loss of will, as well as blight to collective life are as sharp as ever. In the 1844 Manuscript he speaks of capitalism “possessing” its subjects:

Just as in religion the spontaneous activity of the human imagination, of the human brain and the human heart, operates on the individual independently of him – that is, operates as an alien, divine or diabolical activity – so is the worker's activity not his spontaneous activity. It belongs to another; it is the loss of his self.6

While the worker was alienated from her/his own actions, this alienation, practiced as factory despotism, was extremely external to her/him and more or less relied on overt enforcement of certain living conditions of the worker. These miserable conditions, acknowledged as such and obvious to all parties involved, meant constant, open struggle by the workers whose consciousness and power of judgment had not yet been subsumed under capitalism as they would be through the intervention of cybernetics in a century's time.

The Autonomists were right in saying that the history of the mutations of capitalism is in fact the history of its self-modification and adaptation to workers’ struggles and the novel approaches employed by the proletariat. Capitalism has changed and mutated and has greatly improved its controlling forces. Indeed, we have now been in the era of the “proletarianization of the spirit” (also “automatisation des esprits”) for decades: “…we turn into simple reflex machines, into mechanized humans…” (Bernard Stiegler)7

If once, during the industrial revolution, “[disciplinary control] dissociates power from the body” (Foucault, 1977)8, then today, under the “proletarianization of the spirit”, we are witnessing the dissociation of intelligence from the mind. While Leibnizian technics and its product, disciplinary control, operated through the production of “docile bodies,” i.e. bodies that “may be subjected, used, transformed and improved” (Foucault, 1977)9, the proliferation of cybernetic technics now substitutes the machine-like body (which has as its model “the celebrated automata” of earlier centuries) with actual machines, intelligent machines that are the exosomatization and technical realization of the docile, habituated muscular apparatus that is the body. Now, control becomes vaporous and einzelartig (singularity-based, singularized) and it is the mind, which becomes the site of power, manipulation, and control, and all spatially oriented forms move onto a purely temporal register, wherein the pattern of movement or behavior of each “haecceity” allows for the simultaneous maximization of control and fluidity. All categories of space are obsolete in the workings of the Cybernetic Organon as the hydraulic model supersedes that of disciplinary control and accelerates manipulation to a new level of speed (a level achieved only recently through the cybernetic machine, the level of “machines working at the speed of light,” the level of high-frequency-trading algorithms that instigated the flash crash).

The gaseous network of Cybernetic Capitalism is entirely temporal exactly because it is based on amorphous circulation. Any “locality” or nodal specificity is defined in the “pathological” terms of delay and/or conversion inefficiency. Indeed the processes of liquification and becoming-fluid now extend to the human population as well, the immigrant being, the counter-current of capital, circulating in torrents towards centers of development for the establishment of the Marxian free labor-free capital connection. Whether or not such connections are still possible, or efficient is very much a question of historical outlook, contingent upon the workings of the emerging war machine of Neo-Fascism or what I have called “schizo-populism.” The competing strategies of the Fascist war-machine and Cybernetic Capitalism are going to collide at some point and the result is yet to be thought through.10

Quotes Plasticity

A Conversation Between Two Hunters, from Cesare Pavese’s Dialogs with Leuco11

1st Hunter:

… And in one respect, they’re like gods: they have no sense of guilt.

… I never heard of a plant or an animal that wanted to turn into human being. Whereas these woods are full of men and women who were touched by divinity and became bush or bird or wolf. No matter how evil they were or what crimes the committed, their hands were cleansed of blood, they were freed from guilt and hope, they were forgot they were human. …

2nd Hunter:

… Even if the animal has no memory of the past and lives solely for his prey, for death, the thing he was remains.

… The gods add nothing, take nothing. All they do is touch you lightly–and nail you where you are. What once was wish or choice, you find is fate. That means becoming a wolf.12

The Becoming-Shoggoth of the Human Organism

[Shoggoths are] certain multicellular protoplasmic masses capable of molding their tissues into all sorts of temporary organs under hypnotic influence and thereby forming ideal slaves to perform the heavy work of the community. (Lovecraft’s At the Mountain of Madness)

The affective hijacking of a subject’s body, as evinced by Lovecraft, is one of the most efficient and reliable forms of control, which in fact provides a deeper handle on the individual. Protevi has revealed the way anger can be exploited by the military as a “political affect” in the control of soldiers and groups. The subjectivity of the individual soldiers are short-circuited in favor of efficient command-following and group behavior; that is why some soldiers cannot reconcile their own actions in war with their own choice or ethical stance and feel guilty.13

Lovecraft’s works present us with numerous cases of individuals “driven mad” by an affect (fear) so strong that it shears the consciousness, the plasticity of brain that constitutes the basic condition of the autonomy and conscious existence of a human organism. There is a logic of “the Outside” at work in these fantasies: there is a stimulus, a perception, an intrusion from the outside on the organism that is so “outré” and unforeseen, as to shatter the defensive skin of habit that keeps the organism from being consumed in the flows of experience and merging with the Outside. Once that protective membrane has been ruptured, there can be no return to “sanity”. At this point, “he has lost in fear the memory of his name”, (from Donald Tyson’s Necronomicon), or rather the habitual basis of identity necessary for continuity and ipseity.

So, in the mythos of Lovecraft and his followers, we encounter this affective shattering of the conscious subject through the horror-inducing experience of something entirely alien that manages to rupture the membrane of habits by its sheer novelty or otherness. Lovecraft was “oedipal” enough to consider the resulting condition (such as that of the Alhazred) as unsavory and extremely undesirable.

Thus is the logic of plasticity tied to the maximization of potentiality in capital. Cybernetic Capitalism is non-Leibnizian in its abandoning the concept of efficiency as compression and instead seeking to realize the maximum number (all) of potentialities in a temporal register (instead of the spatial dimension of Leibniz). In this it resembles the God of Descartes and the Occasionalists (who, according to Leibniz himself is an idiotic God that takes all shapes during all time, an infinite Proteus, a mad Shoggoth, or rather Azathoth, Lovecraft’s blind idiot God). This is the logic of the Cybernetic Organon as it seeks to maximize the consumer and the efficiency of the human in general. Now, we all must “be fruitful and multiply”: miosis, but not in space but through time, this is the essence of the schizophrenia that is sweeping the prosumer-masses. Realize your maximum potentialities, in a maximal number of ways by not being determined by your determinations. Always be ready to forget, to re-create, to start again, to adapt, to become, to remain open, to be nothing but a this (at once as all these), a most empty determination that is a mere pointer. This is the ideal of capital; this is the prosumer as shape-shifter. The potentiality realized will no longer close its counterparts (bound together, minimally, by the rule of non-contradiction).

This is in no way to be considered a mere figure of speech. These forms, although ideal and only approachable, are in full operation and in full production and have been so for some decades. No, for indeed this and the different forms in which the Cybernetic Organon has propagated itself through all domains of life are first of all a technical and economic reality.

It is very important to know that this critique of accelerationist principles and dreams is not done in the name of retrieving or reviving some form of human decency or sense of honor or other conservative notion of how things ought to be. To repeat the words of an anonymous collective writing in the same vein:

What is at stake in this accelerating replacement of real relationships with robotic proxies is not a loss of some authentic human need, but the eradication of any alternative to individual neoliberalism. (Anonymous, Robot Seals in Short-Circuits: A Counterlogistics Reader)

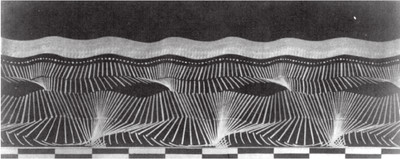

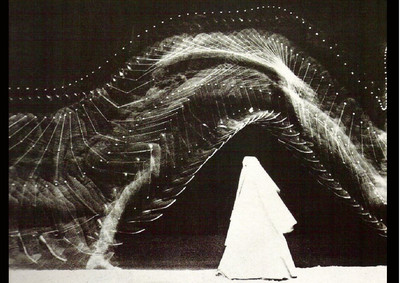

We are dealing with a destruction of the task of becoming-human as becoming-species. Thus the spiritual (geistig) task of self-consciousness qua negation of negation and the infinite re-establishment of the originary I=I becomes the machinic and procedural accumulation of behavioral data (an accumulation of behavior in the temporal register, a chronophotography of all possibilities superimposed, as it were).

Thanatomanic Creativity

As cybernetic machines are taking over more and more of the semi-creative tasks, as the once “mental” tasks requiring human operation become increasingly automated (when the tertiary service sector is itself proletarianized and automated), the value and the meaning of creativity is changed (Bernard Stiegler, 2015).

The spontaneity that becomes an obsession in a Cyber Capitalism of ever-expanding automation is ontological in its core. It is death that is at the center of this new conception of creativity: Metis and Proteus (see Malabou on the distinction) can “create” themselves into almost anything; theirs is a most multitudinous menagerie, but still denumerable and finite. Proteus cannot become a dead body, cannot die and then metamorphose into something else. Death is the very end of creativity and plasticity but in order to truly create, to go beyond the finite bestiary of Proteus, one has to get close to death, as close as humans can get. There is no denying that there is something Greek about the death that is schizophrenic creativity for it drinks of the sweet waters of Lethe and its true name is oblivion.

This is why Deleuze’s image of full human potentiality, the potential to become anything or anyone is the “homo tantum” (Deleuze, 1997): the dying human being whose supposedly “bare life” so close to death loses all of its specificity and singularity to become so generic as to be able to become anything. Straub-Huillet have cinematically realized a dialog from Cesare Pavese, where the question is this: does Lycaon (wolf-man)14 suffer from the metamorphosis he underwent as a punishment from the Gods? Can he suffer if he is truly a beast and remembers not who Lycaon was and what he had done?

What makes a certain remark in one of Turing’s works unique with respect to our own concern is the fact that it sets the criterion on the ability of human minds to change their computation-algorithm in fundamental ways. By engaging in essentially new methods of calculation, human mathematicians are able to compute different portions of the incomputable number δ while the computer, the a-machine, being unable to change its essential algorithm will not be able to compute the said number. Here too, the human aspect is defined as the ability to stop and reflect, to design a new strategy or method newly adapted to the problem at hand, and then embark upon another mechanistically-reproducible path of pure computation. It is this very distinction that is being removed with the emergence of different sorts of adaptive cybernetic devices (including genetic algorithms and neural-networks) designed specifically with the aim of non-stop real-time calculation that has an inner capacity of creativity and change of strategy.

Perhaps the ultimate creative act, the ultimate decision to make at the moment of absolute spontaneity and the full potential of self-determination, is to die. The transformation from the living into the dead is the (only?) perfect creative act in which nothing of the old remains in the new. Perhaps this is the fascination of zombies; they are the post-life organisms that are a completely new being from the person to whom their bodies had once belonged.

Beside death, there is always a limit where humans are concerned. A limitation through their subjectivity and their concept, to use Hegel’s terms:

[t]here is present in each human being, although universally unique, a specific principle that makes him human … if this is true, then there is no saying what such an individual could still be if this foundation were removed from him.15

In fact, the wholly generic state, the blank slate from which absolute creation might be attempted, if at all possible, is only possible for the cybernetic organ. That is why from another aspect, Deleuze’s evacuated subjects resemble machines, as Badiou rightly called them “automata”.16 Meillassoux’s philosophy of contingency17 is the perfection of the Cybernetic notion of apocalyptic creativity and de-singularization (the process by which any specialization or adaptation to a previous milieu is nullified). His explicit rejection of the principle of sufficient reason and the unleashing of the full force of Humean radical empiricism marks him as one of cybernetic philosophy’s vanguards. Meillassoux is the true philosopher of the apocalypse who finally dares to bring the conclusions of schizophrenic creativity onto the plane of the physical reality and in the name of a dead world (the world before givenness) erects the universe into a system of absolute virtuality where the next moment is in no way constrained by the memory of the past ones.

Returning to the issue of amnesia and flexibility, we realize how the cyber-capitalist fantasies of maximum efficiency and frictionless circulation link up to the vaporousness of the Schizo. Basically stated, the machinic standards of capitalism require a smooth network of flattened nodes that can be made to recalibrate and re-adapt instantly and efficiently to any change in the milieu (this is what Deleuze and Guattari call “microperceptions” (Deleuze & Guattari, 1983)). In such a frictionless network there is no room for a reflective consciousness, given how consciousness, per Bergsonian definition, is duration and hence delay.

The dream circuit of capitalism is not an exteriorization or exosomatization of memory, as Stiegler holds, but rather an exteriorization of non-representational behavioral patterns; a network of hijacked habits. These hijacked and completely resettable habits—cybernetic distortions of human habits—are un-conscious, processing stimuli and responding without reflection – “the obscure intelligence that through habit comes to replace reflection” (Ravaisson, 2008).18 A non-representational intelligence that is exosomatized as the cybernetic machine, the feedback driven organ bridging the generic and the hyper-specialized. There is, however, a source of great friction disrupting the realization of the ideal circuitry: Neurosis. As a looping back process of accretion and scabbing responsible for the production and emergence of a crude subjectivity (“how does the mind become a subject?” (Deleuze, 1991)19 to which Charles Johns provides a good answer: “neurosis is precisely that which guarantees experience”20) from the constant flow of data. Neurosis is the purest form of habit-formation and habit-conservation in human organisms (“Neurosis is precisely that which shows itself to us in everyday consciousness; the desperate reflexes and associations we have” (Johns, 2016)21). It is that which allows for a minimum identity and continuation of the subject and it is, by the same token, what severely limits vaporization and adaptation, barring the realization of true schizophrenia.

Plasticity-Vaporization

In animal studies, neural activity related to sensory stimuli can be recorded in many brain regions before habituation. After habituation sets in (a time when humans report that stimuli tend to fade from consciousness), the same stimuli evoke neural activity exclusively along their specific sensory pathways. These observations suggest that when tasks are automatic and require little or no conscious control, the spread of signals that influence the performance of a task involves a more restricted and dedicated set of circuits that become ‘‘functionally insulated.’’ This produces a gain in speed and precision, but a loss in context-sensitivity, accessibility, and flexibility. (Laureys & Tononi, 2009)22

Unlike memory representations, habit memory representations are relatively inflexible, and are acquired gradually over many trials through feedback. (Gazzaniga, 2014)23

There is a deep affinity between the dead and the machinic when it comes to creativity, the creation of novelty; an affinity that is not reducible to their shared character of non-life. If creativity is the creation of an alterity, an act of spontaneity and a whim through which an other “without genealogy” (Malabou, 2012)24 comes to be, and if an organ(ism) creates itself into something new through an instant of self-determination, then by necessity that acts is a near-death experience; there is something of death in every spontaneous (self)creation. Spinoza mentions the zombie-poet Góngora, in his illustration of a death that is not actually dying but the emergence of new structures, new “ratios of motion and rest” (Spinoza, 2000)25 between the parts, of novelty in a body that can no longer be the same. The amnesiac is a popular and necessary figure in this Thanatology of creativity, yet one which pales against the competition the cybernetic machine.

Malabou is precise in her qualification of “plasticity” by the term “destructive” (Malabou, 2012).26 For in that long tradition that conceives of novelty and creativity as a second birth (by non-pre-determined acts), the less background and “genealogy” there is, the less limited the scope of creativity and the potentiality of the emerging novelty. In order to become a new human being, one usually needs to become an amnesiac. It is only through “destructiveness” that human plasticity is sheared, yielding into vaporization; it is only in the second birth, birth of “spirit from spirit” that the agent, the organism, gets to become wind: “The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound, but you cannot tell where it comes from or where it is going (John 3:8).”

While Proteus operates in a loop, always circling back to its initial form after N transformations (Malabou, 2012),27 the radical forgetting in an ideal Carnot Engine of somatic memory is absolutely irreversible, final. The resulting sequence is the birth of a machinic tabula rasa, a Body Without Organs: absolutely amnesiac.

The essence of cybernetics lies in the discovery of machines that (based on feedback mechanisms) are able to change their behavior by sensing their environment and the effects of the actions upon it. The cybernetic machine moves from an “untrained” generic state, where everything all is potentiality, into a fully singular, fully adapted state where its behavior is completely “fitted” to the milieu (the AI gamer of DeepMind would be a good example of a recent model). Only, in case of the cybernetic device, in contrast to the Leibnizian machine, “overspecialization” does not “lead to death” (famous phrase from The Ghost in the Shell franchise), since it does not result from pre-meditated design and is also fully reversible, instantaneously. In principle the cybernetic organ can kick its old “habits” with the most fluid ease.

This singularized vaporousness afforded by the Cybernetic Organon changes the essence of creativity. The never-functioning procedures of individuation through education (adaptation) and un-individuation (universalization) meant to ensure maximum efficiency for each individual throughout time is made simply unnecessary by the Cybernetic Organon’s short-circuiting of individuation and the direct, instantaneous bridge it makes between the absolutely singular and the wholly generic. With cybernetic organs, creativity is not even in need of a milieu to which to adapt. Indeed Wolfram’s experiments on a “simple programs”28 in the contours of his “new kind of science” have shown that the capability of the isolated cybernetic organ for the creation of randomness (read novelty) is in fact greater than systems in touch with an outside “nature” that is random of its own (or, as can always be argued, assumed random due to gaps of knowledge).

This resetting of the "dividual", made in the image of the Cybernetic organ, of the silicon "memory", is done both in favor of the saturated Market (running out of consumers) and as a control measure: fostering instant adaptivity; one who cannot remember cannot think ("reflect").

Unless great, unethical progress is made in biotechnology and mnemotechnics in a literal, visceral sense, such a resetting of the body simply cannot be accomplished. The recalibration of deep-seated habits is so time consuming and complicated that it must not be thought of in terms of the phenotype, but subsets of the genotype: nations, races, tribes. This is already in progress and (in)famously designated as cultural globalization.

From now on, the human is addressed as the pointer to her own habits, for above such bodily, non-conscious, or deep-seated, extro-amnesiac habits as left or right handedness, muscular memory (riding a bike, using a gun), there is no more fixed handle on each Singular human. Above these, the so-called subjectivity of each human has become a most fleeting thing, a pointer with an expiration date. This is why from now on, it is the habits that are spoken to, it is the unconscious body that is addressed in all seriousness, and it is they who must bear the cost and consequences of the actions of the Protean subject-mass of the Singular human.

The cultural obsession with the amnesiac, depicted in countless movies, novels, comic books, etc. is a symptom of the pressure to be creative, to be reflexive enough to deal with our precarious lives. But also tests, thought experiments to find out what is left after the erasure of personality, what constitutes the core stability of a human being if the subjective existence can be wiped. The answer, we know, is the bodily, the non-representational habits as an Ur-Neurosis. The question seems sinister because it is Capital’s question: what is the core that is not flexible, that cannot be easily assimilated and re-assimilated, specialized and de-specialized as the need arises?

A History of Violence (Cronenberg, 2006) is a habituation of violence, an ineradicable set of reflexes at the lowest level of intelligence, burned into the biological existence of the organism. That which lies beneath consciousness (“the unconscious is the body” (Serres, 2011))29 cannot be overcome by change of identity, the latter having become removable, interchangeable, a commodity available at your neighborhood outlet.

Hardcore Henry is driven by love. The strange first-person film is an experiment in the power of affects in control and motivation of action (even or esp.) in absence of memory, as the eponymous hero wakes up an amnesiac, apparently tended to by his wife. It is a desire for his “wife,” it is his love for her, that controls and drives him, “assimilates” him (Johns, 2016),30 his affects being handles for his manipulation, handles for accessing the potentialities of the weaponized body. More than a tale of brainwashing, it is a story about short-circuiting consciousness through affect, aiming at absolute predictability and control. The affectively controlled, manipulated body can be weaponized much better than the conscious subject who always has some background, some essential habits and neuroses, tendencies and traits that even years of military training will not erase or over-write. The residual neuroses can become an element of potential catastrophe in the field of battle where the body is weaponized and placed under command, performing without hesitation, without reflection. Hence the extensive feelings of guilt and astonishment over atrocities committed (Protevi, 2013).31

The Schizo is always “in it” or is encouraged to be: immersion, virtual submersion. As the distinctions between labor and leisure become increasingly meaningless, the ideal form of “prosumption” must become “effortless” while being simultaneously creative and “out there.” If Ravaisson was correct to state that it is effort that builds the individuation spectrum through habit, then we have to consider the implications of an effortless existence where creative processes become habits and habits become exo-somatized, delegated to machines that cut off the human from the world in order to ensure “frictionless” circulation of flows:

The subject experiencing pure passion is completely within himself, and by this very fact cannot yet distinguish and know himself. In pure action, he is completely outside of himself, and no longer knows himself. Personality perishes to the same degree in extreme subjectivity and in extreme objectivity, by passion in the one case and by action in the other. It is in the intermediate region of touch, within this mysterious middle ground of effort, that there is to be found, with reflection, the clearest and most assured consciousness of personality. (Ravaisson, 2008)32

This immersive life of the schizophrenic is recognized and described by psychiatry as the “disturbance of ipseity (or minimal self).” The minimal self is defined as that which underlies and guarantees the perception of experiences as “my experiences,” endowing the self with a certain minimal universality that enables it to stand above and transcend each immediate experience-flow. This insight of psychiatry repeats Hegel’s anthropology of the “soul” and the emergence of the spirit from organic existence. From the effects of the Cybernetic production of “the World” in real-time, we can see how, when “effort” is replaced by the divine connective touch of the cybernetic protocol, the reflective self, the “most assured consciousness of personality” is unmade and rendered indeed impossible. Without phronesis, there can be no subjectivity and no reflection, which is to say, no autonomy. The delegation of small but proliferating tasks to cybernetic machines cuts off the individual from its engagement with the world and thus from the practical judgment that lies at the heart of autonomy. With artificial intelligence making our lives “more convenient,” we approach a state of non-autonomous existence where consciousness becomes detached and obsolete, folding in on itself in its isolation.

- This is an important topic: the relation of human time and the machinic time of cyber-capitalist circuits of valorization.↩

- Spinoza describes a poet who, undergoing a certain illness, was so changed as to be unrecognizable. Spinoza suggests that this constitutes a form of death since death is a complete rearrangement of parts and as such the poet is said to die because none of his original construction remains.↩

- Even in the case of H. M. however, the learning that is habitual was partly intact, and new skills could well be learned.↩

- Bernard Stiegler replying to Ariel Kyrou in 'Bernard Stiegler, interviewed by Ariel Kyrou', Mille et une nuits, département de la Librairie Arthème Fayard, mai 2015. Translated from the French.↩

- 'Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works Vol. 3', Lawrence & Wishart Electric Book, 2010, p. 275.↩

- ibid. p. 274.↩

- 'Bernard Stiegler interviewed by Ariel Kyrou', Mille et une nuits, département de la Librairie Arthème Fayard, mai 2015, p. 8. Translated from the French.↩

- Michel Foucault, 'Discipline and Punish, The Birth of the Prison', trans. Alan Sheridan, Vintage Books, New York, second edition, 1995, p. 138.↩

- ibid, p. 136.↩

- On this see Alliez and Lazzarato’s 'Guerres et Capital' or its introduction, which is already available in English.↩

- Cesare Pavese, 'Dialogues with Leucáo', tran. William Arrowsmith and D.S. Carne-Ross, Peter Owen Limited, London, 1965, p. 78-79.↩

- This is the non-Deleuzian model of becoming. This is the real form of becoming-species. This demonstrates the back-tracking of new truth onto the history of creation so as to appear primordial: a destiney. A monster can always become the realization of a prophecy just as a contingency, an artifice, will dream itself into a historical inevitability.↩

- In terms of consumer experience, this becomes what Stiegler calls the “desublimation” of seduction and thus also of desire. This trend in marketing is in fact the reverse of the Freudian process of sublimation in that the symbolically-mediated operations of the libido, the sex drive, are more and more replaced for the direct and pornographic depictions that are purely sexual. In this bid to get closer to and gain better control over the body, the forms of the libidinal economy break down along with the obsolescence of the function of the libido. The result, of course, is the emergence of “l’économie pulsionnelle” or “drive economy.”↩

- In Greek mythology, Lycaon is the king of Arcadia who tries to trick Zeus into eating human flesh. Zeus is not deceived and turns Lycaon into a wolf.↩

- G.W.F. Hegel, 'The Science of Logic', trans. George Di Giovanni, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, p. 16.↩

- Alain Badiou, 'Deleuze: The clamor of being Theory out of bounds', trans. Louise Burchill, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2000.↩

- Quentin Meillassoux, 'After finitude: An essay on the necessity of contingency', trans. Ray Brassier, Continuum, London, New York, 2008.↩

- Felix Ravaisson, 'Of Habit', trans. Clare Carlisle and Mark Sinclair, Continuum, London, New York, 2008, p. 55.↩

- Gilles Deleuze, 'Empiricism and Subjectivity, An Essay on Humes Theory of Human Nature', trans. Constantin V. Boundas, Columbia University Press, New York, 1991, p. 23.↩

- Charles William Johns, 'Neurosis and Assimilation: Contemporary Revisions on the Life of the Concept', Springer, Lincoln University, UK, 2016, p. xix.↩

- Ibid, p. 6.↩

- Steven Laureys and Giulio Tononi (eds), 'The Neurology of Consciousness: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropathology', Academic Press, Amsterdam, Boston, 2009.↩

- Michael Gazzaniga, (ed.), 'The Cognitive Neurosciences', MIT Press, Massachusetts, 2014.↩

- Catherine Malabou, 'The Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity', trans. Carolyn Shread, Polity, Cambridge, 2012.↩

- Baruch Spinoza, 'Ethics', trans. G.H.R. Parkinson, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000.↩

- Catherine Malabou, 'The Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity', trans. Carolyn Shread, Polity, Cambridge, 2012.↩

- ibid.↩

- Stephen Wolfram, 'A New Kind of Science', Wolfram Research, Illinois, US, 2002.↩

- Michel Serres, 'Variations on the Body', Univocal, Minneapolis, 2011.↩

- Charles William Johns, 'Neurosis and Assimilation: Contemporary Revisions on the Life of the Concept', Springer, Lincoln University, UK, 2016.↩

- John Protevi, 'Life, War, Earth: Deleuze and the Sciences', Minnesota University Press, Minnesota, 2013.↩

- Felix Ravaisson, 'Of Habit', trans. Clare Carlisle and Mark Sinclair, Continuum, London, New York, 2008, p. 45.↩