“The colonial world is a world cut in two. The dividing line, the frontiers are shown by barracks and police stations. [...] The zone where the natives live is not complementary to the zone inhabited by the settlers. The two zones are opposed.” (Frantz Fanon)

Frantz Fanon understood that colonial violence is inscribed in space. He was describing colonial space, yet, reading his quote today, it is the image of the French post-colonial banlieue that comes to the fore. Léopold Lambert has investigated the geography of Paris and its banlieues, concluding that we must talk of a “Fortress Paris” when it comes to the spatial relationship between the capital and its economically weakest suburban districts.

Since the riots in 2005 this urban divide has intensified with militarization of urban areas, intensified gentrification of areas close to train stations and the withdrawal of public as well as social institutions and services in the banlieues. The political response to the riots from the third-way left (Parti Socialiste) closely tied in with the perspectives and voices heard on the right, each of which called for the further empowerment of the police. After 2005, as Hacène Belmessous demonstrated, the police became a major partner in urban renewal and were directly involved in the control and surveillance of public and in some cases even semi-public space (lobbies, corridors, elevators). Other questions dealt with the placement and construction of roads, the reduction of public space and the methods used in the policing of different areas.

This is where urbanism as a specifically military problem became apparent (again) while those living in such areas began to firmly construct (or reject) the corresponding identities imposed on them by the governing apparatus. This development is hardly surprising, in fact it is a historical revision taking into consideration that these post-war modern estates (villes nouvelles) were planned and executed by the post-colonial French state. During the 1950s, the politics of planning in France was underscored by the coincidence of decolonization and an urbanization boom. The villes nouvelles, controlled by the state through the new administration of the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, were implemented by white collar professionals recruited from the former colonies in North Africa. Because of the turmoil in the Maghreb – riots in Casablanca hat lead to independence struggles – administrators, planners and architects, returned to France to key positions in the Caisse des Dépôts, developing and applying the planning approaches and design mechanisms that they had experimented with on colonial grounds. Hence, military logic and control – as both purpose and tool of urban planning – consciously and unconsciously migrated from the Maghreb into the design of the villes nouvelles from the start, at the same time that the migration of people from the former colonies to French cities took place.

The programmatic restructuring of space and its militarization happening since 2005 are merely a revised continuation of the colonial, binary planning logic of “us” and “them”, of controlling entities on the one hand and controlled bodies and spaces on the other, in the form of urban renewal and under the neoliberal doctrine. It reinforces, even intensifies the very dividing line, the post-colonial frontier that has escalated into riots in the past. It is installing a neo-colonial violence inscribed in space.

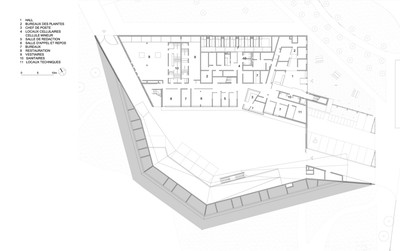

With political and social services increasingly removed from the banlieues since 2005, police stations are sometimes the only remaining public buildings, standing out more than before. In the case of Clichy-sous-Bois, where the riot broke out in 2005, mayors had been asking for a police station for 30 years. After the riot of 2005 it was decided that they would get one.

In the documentary film La Sociologie est un sport de combat (Pierre Carles, 2001), there is a scene at the very end in a cultural center in the banlieue Le Val Fourré, where Pierre Bourdieu holds a discussion with a young inhabitant, Said, who says:

“We ask for cultural centers and they give us a big police station, with these statues out in front, to claim that they too know culture. But if you take away the statues, you know what you’ll see? Nothing but a police station and the brutality it represents.”

The police station in Clichy is more sophisticated. It’s not a functional, honest building with a sculpture/statue in the front. Rather, it comes in the disguise of a sculpture itself. Removing the sculpture in order to see the brutality that the police station represents is not possible anymore.

The police station in Clichy looks like a cultural center, a sculpture an architectural monument. The architectural language is clearly borrowed from the cultural realm and a tendency in architecture towards more monumental forms and “sculptural” expressions in the 1990s and 2000s.

Most of the police stations reinforce a “brutal” or “weaponized” antagonism from within and from without, this one, and to a lesser degree few others, also reinforces a cultural antagonism from outside that distinguishes itself in terms of material, formal expression and style vis-à-vis the HLM buildings (Habitation à Loyer Modéré, French public housing) in the neighborhood. The police, as a public authority, doesn’t just seem to appreciate culture in the form of a statue in front of the building, it seems that they are “cultured” and therefore superior. Here also the financial aspect is important: the building cost twice as much as a regular police station, €11.360.000 (compared to the one built by XTU in Saint-Denis around the same time).

The building represents a kind of victory for the police after the 2005 riots. Here a single, official narrative of power brings us back to the urban logic of the banlieue and the history of colonial urbanism in the Maghreb. The binary this building seems to reproduce – police vs. rioters, and in spatial terms, police station vis-à-vis the HLM blocks – is more than a weaponized antagonism. It is also a cultural antagonism.

However, this represented binary “police vs. rioters” is false, since they are not equal rivals – there is an asymmetry of violence and control. The image of the binary is an ideological tool in itself, reproducing the status quo “us vs. them”, police vs. HLM/rioter. However, the HLM we see in this picture is, like the police station, a state building. The banlieue space, in the form of the HLM, is a space produced by the state. The state conceived its modern planning principles in the colonial context in the Maghreb. It implemented it in France, and controls, manages, renews and demolishes or privatizes it, raises its rent or manages its decline. It disconnects it from infrastructures or public services as much as it connects it to public services, in this particular case: to the police station.